Who pays? You do

Hazards 106, April - June 2009

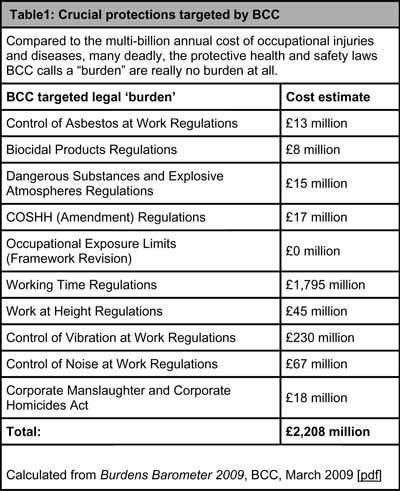

When the British Chambers of Commerce (BCC) published its ‘2009 Burdens Barometer’ in March 2009, it put the cumulative cost to business of regulations introduced since 1998 at £76.81 billion (1). Included on its ‘burdens’ list are 10 workplace safety regulations covering working time, chemicals, asbestos, explosives, biocides, work at height, vibration and noise, as well as occupational exposure limits and the corporate manslaughter act [see table 1].

Together these health and safety measures created, by BCC’s calculation, a cumulative burden on business of over £21.5bn – 28 per cent of the total - with a recurring annual cost of £2.2bn. But it is only in the small print that BCC mentions its calculation is “net of the benefits that accrue to business.”

BCC director general David Frost, ignoring the potential benefits of having fewer dead, sick or injured workers or of the near universal recognition that light touch financial regulation ushered in the current recession, said: “The government needs to get serious about reducing the massive burden of regulation on business.

“Cutting unnecessary burdens and announcing a moratorium on new regulations set to come in this year, is one way of providing instant and inexpensive help to British firms.” But this BCC argument discounts significant benefits to business, in reduced sick leave, retention of trained and productive staff and, potentially, avoidance of safety fines, compensation payouts and spiralling employers’ liability insurance costs. And it ignores entirely the human cost of poorly regulated workplaces.

Calculated response

A May 2006 government regulatory impact assessment put the total cost of non-asbestos occupational cancer deaths each year at between £3bn and £12.3bn (2). It put the cost of each occupational cancer, at 2004 prices, at £2.46m. Since the estimate was published, the government has conceded it has under-estimated the number of occupational cancer cases each year, so by inference has under-estimated the cost.

And the multi-billion pound annual occupational cancer bill – even the low estimate is higher than the annual cost of the safety laws targeted by BCC - excludes the cost of asbestos cancers, which the government says outnumber all other forms of occupational cancers combined. This makes BCC’s business burdens-only gripes about the annual cost of the Control of Asbestos at Work Regulations of £13m and of the Control of Substances Hazards to Health (Amendment) Regulations of £17m seem misguided at best.

Through the eyes of a workplace cancer victim or a bereaved relative, it could be seen as a downright murderous misrepresentation of the real situation.

What Barney’s death cost my family

Ralph ‘Barney’ Kennedy, 24, died instantly when he touched the live metal casing on a light fitting during improvements work on a Camden Council housing block. An investigation into the September 2006 fatality found someone had cut the earth cable to the light, possibly to stop it flickering.

In March 2009, the council was fined £40,000 and ordered to pay costs of more than £16,000. Barney’s partner, Kelly Ivory, was left to care for their two infants, Bailey and Bethany (above). At the time of his death, Barney was working extra hours to pay for a puppy to give to Bailey on his birthday. Kelly said: “The children both talk about Barney. He would always take them to the park and the zoo. I miss him.”

The impression is reinforced when you look at the cost of occupational injuries. A 2008 Health and Safety Executive (HSE) economics briefing put the total cost of each occupational fatality – and there’s hundreds every year - at £1.5 million (3) [see table 2].

If you add in work-related road traffic fatalities, you’d be looking at an annual fatal work injury cost of over £1bn.

Unions were not slow to criticise BCC. Stephen Boyd, assistant secretary of the Scottish Trades Union Congress (STUC), said: “Given that the current economic crisis is the result of weak and ineffective regulation in the financial sector, it is a somewhat strange time for the Chambers to proceed with publishing its ‘Burdens Barometer’.” He asked whether BCC’s hope was for business to be “free to jeopardise workers’ health and safety” and other protections.

TUC general secretary Brendan Barber said: “This tired stunt is well past its sell-by date.” He added: “I suppose we should be grateful that the BCC haven't added in the cumulative costs of the abolition of slavery and stopping children cleaning chimneys.”

Compared to the multi-billion annual cost of occupational injuries and diseases, many deadly, the protective health and safety laws BCC calls a “burden” are really no burden at all.

Cost shifting

But while BCC is over-estimating the cost to business, it is discounting entirely the cost paid by the victims of slack health and safety standards. And this human price out-strips the business cost several times over.

A 2004 HSE report, using 2001/02 figures, put the cost to society of occupational ill-health and injury at between £20bn and £31.8bn (4) [see table 3]. Of that, only between £3.9bn and £7.8bn – less than a quarter – was borne by employers, although they were by and large responsible for the workplace conditions that led to the injury or ill-health.

Employers are indisputably the ones bearing the legal duty to minimise those risks “so far as reasonably practicable.”

A 2008 update to the 2004 HSE report concluded: “’Society’ bears the largest cost burden (comprising loss of output, medical costs, costs to the Department for Work and Pensions of administering benefit payments, and HSE and local authority investigation costs), followed by individuals (in terms of loss of income, extra expenditure of dealing with injury or ill health, and subjective costs of pain, grief and suffering).

“Although the costs of workplace injuries and work-related ill health are attributable to the activities of the business... the bulk of these costs in 2001/02 fell ‘externally’ on individuals and society.” (3)

A US study reached similar conclusions, with researchers estimating the split of the burden of occupational illness, injury and death at 44 per cent on the family, 18 per cent on taxpayers and over 27 per cent coming from the employer-financed workers’ compensation system (5). It concluded employers offset their, much lower, costs by “cost shifting” - increasing prices or reducing wages.

An Australian government study published in March 2009 took the opposite approach to BCC and restricted its analysis to the costs of occupational injury and illness (6). It said its costs estimate “represents only one side of the occupational health and safety cost equation.

“For example, the costs incurred by employers for compliance with occupational health and safety regulations and prevention activities are not considered within the scope of the current study.”

When you look only at the flesh and blood, anguish and tears burden you get a sobering picture of who is bearing the cost of hazardous workplaces. The study concluded: “In terms of the burden to economic agents, 3 per cent of the total cost is borne by employers, 49 per cent by workers and 47 per cent by the community.”

A hidden victim of employer cost shifting is prevention. If employers do not bear the real human health and societal costs of their hazardous operations, then there is less incentive for them to do anything about it.

Killer firm came out £74m better off

Andrew Hutin, 20, was killed along with two other workers in a furnace explosion on 8 November 2001 at the Corus steelworks, Port Talbot, South Wales. In December 2006, Corus was fined £1.3m, with Justice Lloyd-Jones criticising the company's “casual” attitude to safety.

Andrew's father, Mick (above), said: “Corus has received £75 million from its insurers, which paid in full for a new blast furnace, opened with a huge amount of national publicity by Prince Charles. Could someone therefore inform me, because I am obviously missing something here, who has been penalised?”

In ‘Defending the indefensible’, a 2008 examination of the behaviour of the global asbestos industry, academics Jock McCulloch and Geoff Tweedale note the history of the potent human carcinogen “shows a consistent pattern of duplicity” by the industry “and escalating injuries to individuals.

“In both the OECD states and the world’s poorest countries, the asbestos industry has only thrived because the actual costs of that injury have been discounted or moved out of sight.

“If the disease burden among asbestos workers had been truly reflected in the price of asbestos products, then the global industry would have spiralled into decline in the 1950s.” (7)

But asbestos wasn’t banned in the UK until 1999, and dozens of other carcinogens are still in use in UK workplaces (8).

From occupational diseases to workplace injuries, there is a high price to pay for the unacceptable, unhealthy conditions in many British workplaces. Only a minute proportion of cases of occupational injury or disease result either in compensation for the victim (9) or the prosecution of an employer.(10)

In cash terms, employers get off lightly. In human terms, employers just don’t suffer at all.

We know who really pays

The Herbertson family Linzi Herbertson’s husband Andy was killed aged 29 when he fell from an unsafe scaffold. ”I had to turn off his life support machine on our son’s 8th birthday. The company was fined less than £10,000 and I was on my own with two young children,” she said. “My children are now of an age when they will be going out to work. I live in fear that they will be no safer than their father was as I know that the enforcement of health and safety is very lax and employers have no fear of paying a proportionate penalty and know if they kill someone it’s relatively easy to get off with a fine.”

The Norman family Gordon Field, 58, was crushed by unsafe lifting gear at Armstrong's Steel, Stoke-on-Trent, on 30 October 2000. He died five days later. His daughter, Sharon Norman, said: “Four hours after his accident a safety stand was made at a cost of £12, this would have stopped the lifting gear from falling on him - far too little, far too late.” The company was in business manufacturing the sort of safety equipment which should have been used to protect Gordon. The firm was fined £100,000 for safety offences. “Armstrong’s pleaded guilty but never said they were sorry. I feel someone must pay for this crime. I would have been satisfied if someone had just said sorry to me but nobody did.”

The Sullivan family Mary O'Sullivan, the widow of Patrick O'Sullivan, 54, killed by a falling platform at Wembley Stadium said she was “disgusted” by a verdict of accidental death at his inquest. Carpenter Patrick O'Sullivan, 54, died after a platform fell more than 300ft and landed on him while he was working on the construction of the new Wembley Stadium in January 2004. Mary said: “He was crushed to death that morning. And they crushed us to death as well.”

More case histories: www.hazards.org/deadlybusiness/wmd2009

References

1. Burdens Barometer 2009, BCC, March 2009 [pdf].

2. REACH Partial Regulatory Impact Assessment after Common Position, Defra, May 2006 [pdf].

3. The costs to employers in Britain of workplace injuries and work-related ill health in 2005/06, HSE Discussion Paper Series, No. 002, September 2008 [pdf].

Economic Analysis Unit (EAU) appraisal values, HSE, July 2008 [pdf].

www.hse.gov.uk/economics

4. Interim update of the ‘Costs to Britain of workplace accidents and work-related ill-health’, HSE, June 2004 [pdf]. www.hse.gov.uk/statistics

5. Paul J Leigh, Steven Markowitz, Marianne Fahs, Philip Landrigan. Costs of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses. University of Michigan Press, 2000.

6. The Cost of work-related injury and illness for Australian employers, workers and the community: 2005-06, Australian Safety and Compensation Council, March 2009.

7. Jock McCulloch and Geoffrey Tweedale. Defending the indefensible: The global asbestos industry and its fight for survival, Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN-0-199-53485-3.

8. Rory O’Neill, Simon Pickvance and Andrew Watterson, Burying the evidence: how Great Britain is prolonging the occupational cancer epidemic, International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health (IJOEH), volume 13, number 4, pages 428-36, 2007.

Andrew Watterson and Rory O’Neill. Burying the evidence: How the UK is prolonging the occupational cancer epidemic, Hazards magazine online report, 25 June 2007.

9. A little compensation, Hazards magazine, Number 90, April-June 2005.

10. Where is the justice?, Hazards magazine, Number 104, October-December 2008.

Related information

Peter Dorman. The cost of accidents and diseases, Three preliminary papers on the economics of occupational safety and health, ILO Safework, 2000.

Deadly Business.

A Hazards special investigation

The decimation of Britain's industrial base was supposed to have one obvious upside - an end to dirty and deadly jobs.

In this 'Deadly business' series, Hazards reveals how a hands off approach to safety regulation means workers continue to die in preventable 'accidents' at work.

Meanwhile, an absence of oversight means old industrial diseases are still affecting millions, and modern jobs are creating a bloodless epidemic of workplace diseases - from 'popcorn lung' to work related suicide.

Hazards webpages

Hazards Workers' Memorial Day pages